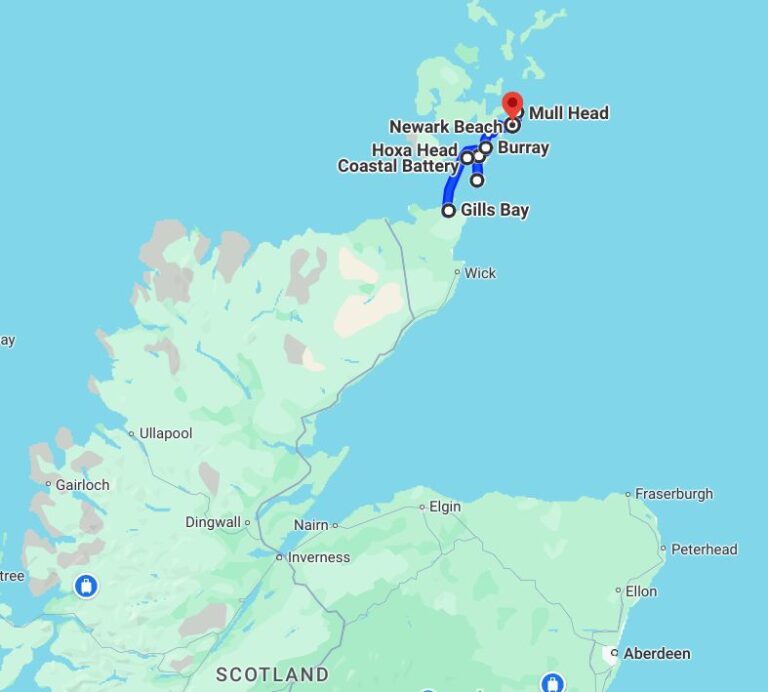

Orkney or Orkney Islands, but not Orkneys (we have read that some locals may get their knickers in a peerie twist upon hearing this) is only about a 90 minute ferry ride from Gills Bay on the Scottish mainland (more on mainland later). The hardest part in getting to Orkney is getting on the ferry.

First of all, you have to back on to the ferry. This means turning around in the ferry parking lot, backing up onto the access way and backing down the access way onto the ramp onto the ferry. Then comes the hard part… backing onto the ferry in-between lorries and/or the steel side of the ferry. After that comes the hardest part, getting out of your vehicle.

We finally got Rosie backed into her spot, but then discovered we couldn’t open the cab doors wide enough to get out. No problem, we will just stay in the cab for the 90 minute trip. Nope. Get Out Of The Vehicle we are told by the ferry load officer. We can’t. Get Out. We can’t. Get Out. It doesn’t look like they are going to let us stay in the cab, so we crawl through the opening from the cab into the back living module to try the side door of the module.

The side door opens a bit more than the cab doors and Brenda makes it out, barely. I squeeze into the narrow door opening and… get stuck (cue the obligatory remarks from the peanut gallery). Brenda is somewhat narrower than I am, so where she can go I can not necessarily follow. Just to round out the picture, the stairs that we normally lower when we want to exit through the side door of the living module are not at this time in the lowered position as there is a post right in the way (see photo above). Because there are no stairs it is necessary to jump down. Brenda makes this jump assisted by a ferry worker. I have not jumped. Or rather I have jumped, but gravity, which usually imparts a downward motion, has been impeded by a portion of my body becoming wedged in the doorway opening.

I briefly contemplate climbing back into the module, but given that my feet are in mid-jump (i.e. not currently touching anything except air) it seems that going back up could be a bit of a challenge. Given that up is out, it seems like down is the only option. Some vigorous squiggling and squirming results in an unceremonious heap of me on the ferry deck. What happened to the ferry guy? Apparently he only does damsels in distress. The rest of us are on our own.

Anyways, we have made it on to the ferry, more or less in one piece. There is no way we are getting back in the way we came out, so we will worry about that later.

Apparently we provided some entertainment for the other ferry passengers. Our backing on to the ferry and subsequent extraction activities had not gone unnoticed.

The ferry trip was far less exciting and we arrived at the ferry dock in St. Margaret’s Hope on South Ronaldsay, one of the Orkney Islands. The ferry workers, perhaps after seeing the look on my face, get the lorry to our left to move out first, thus enabling us to open the driver’s side door and climb into Rosie’s cab. Driving forward off the ferry is much less exciting than backing onto the ferry (which is a very good thing).

We have decided to tour the Orkney Islands from south to north, so we are heading to Burwick, located at the southern end of South Ronaldsay.

On the drive south we stop at a high point to check out the view. As we looked around we noticed that there wasn’t a tree in sight!

Orkney has been continuously inhabited for over 8500 years and apparently there were trees here, but now there are none. Very poor forest management back in the mesolithic and neolithic ages.

Orkney is an archipelago of about 70 islands, 20 of which are inhabited. Some are accessible only by passenger ferries and some ferries are too small to carry Rosie, so we won’t be visiting all of the islands.

The entire population of Orkney is 22,500, with the largest number, 17500, living on Mainland (yes, they really do call it Mainland). This means that the remaining 5000 people are spread out over 19 islands. Here are a few islands and their populations:

- Inner Holm, pop 1

- Tresness, pop 2

- Holm of Grimbister, pop 3

- South Ronaldsay, pop 909

A passenger ferry (no vehicles except bicycles) used to run from John O’Groats (Scotland) to Burwick (Orkney). This ferry is no longer in operation. The ferry business was owned and operated by the same family for over 50 years. They ran the ferry service and wildlife cruises. It was put up for sale (no reason given), but no buyers came forward.

Burwick was the Orkney ferry terminal for the ferry service and there is still a large parking lot where tour busses lined up to receive passengers. The only activity left is a single fishing boat that uses the old passenger ramp.

There is a nice cliff walk from the Burwick ferry terminal, see the photo at the top of this post.

Moving up the east coast of South Ronaldsay we stop in at Hoxa Beach where we can nestle Rosie in for the night amoung some sand dunes.

The storm passes during the night and Rosie weathered it like the champion she is! The next day we are hiking around Hoxa Head, the penisula seen on the right side of the beach photo above.

Hoxa Head is home to a WWI coastal battery that was upgraded and used again in WWII. What is there about Orkney, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, that required protecting in both WWI and WWII?

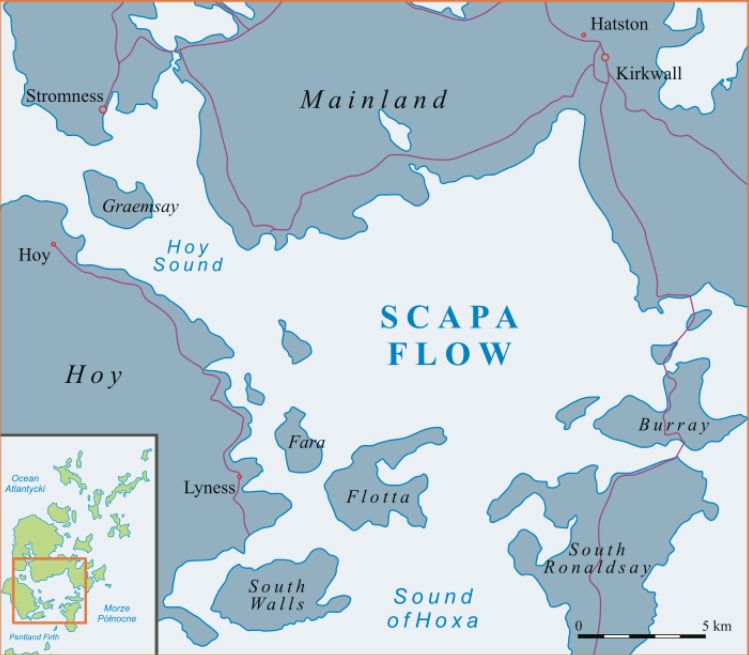

Orkney is home to the Scapa Flow, a body of water protected by the Orkney islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Hoy, Flotta, South Ronaldsay and Burray making it a natural deep water harbour with easy access to both the North Sea and the Atlantic ocean.

The British Admiralty first used Scapa Flow during the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800’s, and Scapa Flow was the main naval base for the British Home Fleet in both WWI and WWII.

As part of the Armistice agreement at the end of WWI the German government had to place most of it’s naval fleet under the watch of the British Admiralty. In 1919 74 German naval vessels arrived in Scapa Flow for internment while negotiations over the final disposition of the German fleet took place. Fearing that the British would arbitrarily seize the German vessels, or that the German government might reject the Treaty of Versailles, the German Admiral in charge of the fleet ordered the vessels to scuttle themselves. 52 of the 74 German vessels sank on the 21st day of June 1919.

Interesting side note: the scuttled German vessels are now used as a source of “low-background steel”. Steel produced after the first nuclear explosions of the 1940’s and 1950’s is contaminated with residual radioactive material. Modern particle detectors, used in experimental and applied particle physics, need to be constructed using only low-background steel.

In WWII the British Admiralty again used Scapa Flow to house the Home Fleet. However, the defences put in place to protect vessels in Scapa Flow during WWI were insufficient against WWII technology. In October 1939 German U-boat U-47 snuck into Scapa Flow, sank the British battleship HMS Royal Oak, and then escaped Scapa Flow undetected.

This was a big wake-up call to the Brits and part of the response was the construction of the Churchill Barriers, a series of four causeways linking Orkney Mainland to South Ronaldsay and cutting off access to Scapa Flow from the east.

The benefit of the Churchill Barriers is that it is now possible to drive from South Ronalsay to Mainland without the need for ferries.

On the way north we cross one of the Churchill Barriers and stop at a beach on the island of Burray in part because it is a nice place to stop (in the dunes above the beach), but also because it is the location of the Viking Totem Pole. The dunes and beach are nice, but the totem pole is underwhelming. The totem pole wasn’t made by vikings, but made by a local artist in 2002 to look like a viking. Meh.

We cross the three remaining Churchill Barriers and are now on the island of Mainland. Continuing north and east we pass into Deerness.

Looking at a map Deerness appears to be an island separate from Mainland, but a small land bridge (natural, not one of Churchill’s) connects Deerness to Mainland, turning Deerness into a peninsula.

The northern-most point of Deerness is Mull Head.

We haven’t encountered many tourists so far, but this changes when we get to Mull Head. We squeezed onto the edge of the parking lot and thought that there wasn’t much room for anyone else… then along comes a full-sized tour bus. The bus stops. Lets everyone out. Then does a 50-point turn to get pointed back down the road. Fifteen minutes later the passengers get back on board and the bus roars off down the road.

It’s been ages since we have been to a beach (ok, maybe a couple of days, but the kids are whining for a beach day), so Newark beach, here we come.