A quick history note:

Prior to 1468 the islands of Orkney and Shetland belonged to Norway. In 1468 the King of Norway pledged the islands as security for the dowry that was to be paid to Scotland for the wedding of his daughter to the son of the King of Scotland. The dowry of 60,000 Florins (about $8 million US dollars today) was never paid and Orkney and Shetland eventually become part of Scotland.

The cupboards are bare, so time to restock. There are not many grocery stores on Orkney, so a trip to the capital, Kirkwall, is in order. Bonus features for Kirwall include: a large parking lot in the middle of town; a campground within walking distance of town; a museum; a cathedral; two palaces and a weird hobbit-house kind of thing. “Kirwall is the place to be” (sung to the tune of “Green Acres”).

After loading up at the Tesco, we set up camp at the awkwardly named “Orkney Caravan Park at the Pickaquoy Centre”. Good place to park Rosie for the night and an easy walk into town.

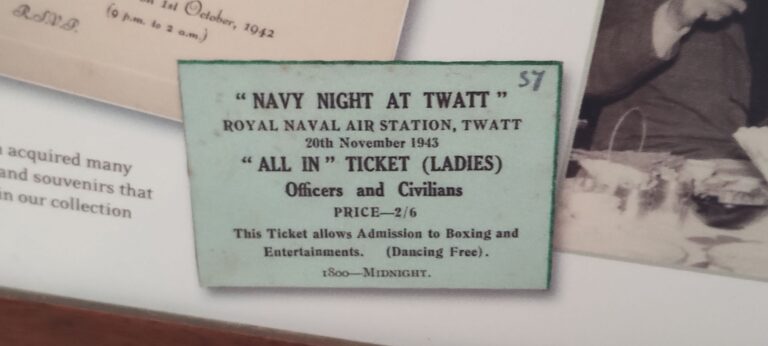

One of the places I am interested in visiting is the Orkney Wireless Museum…

This museum came about because of an enthusiastic collector of domestic and military wireless equipment. After his death a charitable organization was created to manage and display his collection. In 1997 the Orkney Wireless Museum was established in Kirwall, and is staffed by volunteers and enthusiasts.

An incredible collection of old valve (we would call them tube) radios. Most were in glass display cases, so apologies for the poor photos.

The museum also had some non-radio historical artifacts, such as: sony walkman, sony discman, ipod, a collection of boom boxes. The only thing they seem to be missing is an eight track player (anyone have a spare one they could send to the museum?).

Kirkwall has a nice feel to it and has some nice older streets to walk around. The St. Magnus Cathedral is right in the middle of the downtown area.

St. Magnus is the oldest cathedral in Scotland and the northernmost cathedral in the UK. Another claim to fame is that St. Magnus is the only cathedral in the UK to have it’s own dungeon. No “ten Hail Marys and off you go, it’s the dungeon for you my young sinner”. Ahhh, the good Old Testament days.

After the Scottish Reformation (breaking away from the Catholic Church, part of the wider European Protestant Reformation that took place in the 16th century) the Cathedral became part of the Church of Scotland, and is still in use today.

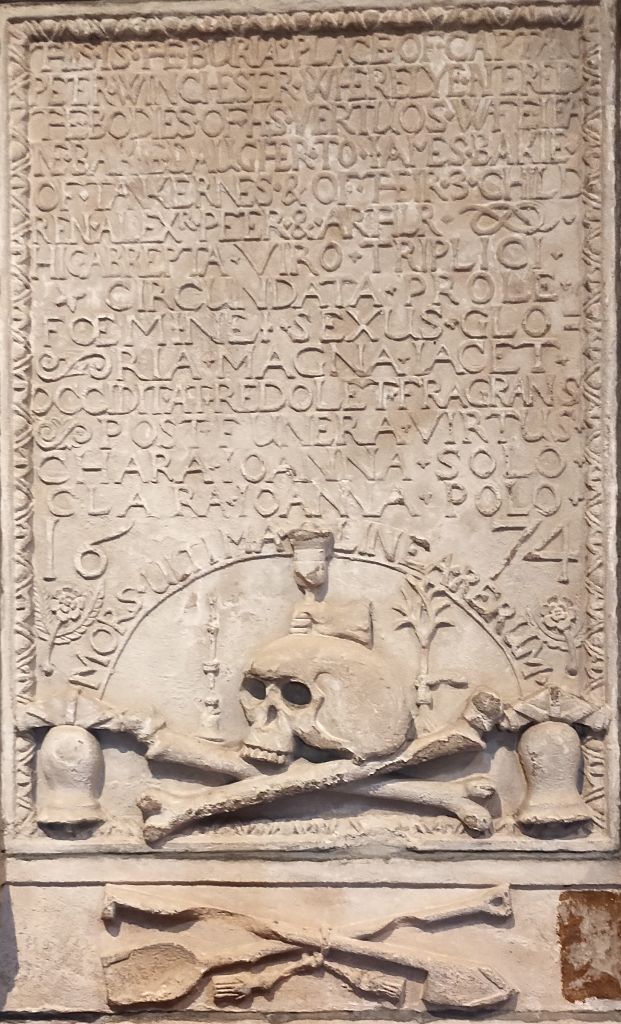

The use of skulls and crossbones on tombstones was popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. Meant as a symbol of death and a memento mori (Latin: “remember you must die”). It is interesting that the skulls and bones are almost comic-book like in style. I don’t think this was due to a lack of artistic ability as this style is found on many tombstones of this period.

Right across the road from the Cathedral are two palaces: the Bishop’s Palace, and the Earl’s Palace.

The Bishop’s Palace was built in the 12th century at the same time the Cathedral was being built. It housed the Bishops of Orkney who were the ecclesiastical heads of the Diocese of Orkney, a medieval bishopric (a district controlled by a diocese) of Scotland. Medieval bishops were considered nobility (hence the palace) and were well educated and wealthy. The last medieval Bishop of Orkney, Robert Reid, provided the foundation for the University of Edinburgh through a bequest in his will.

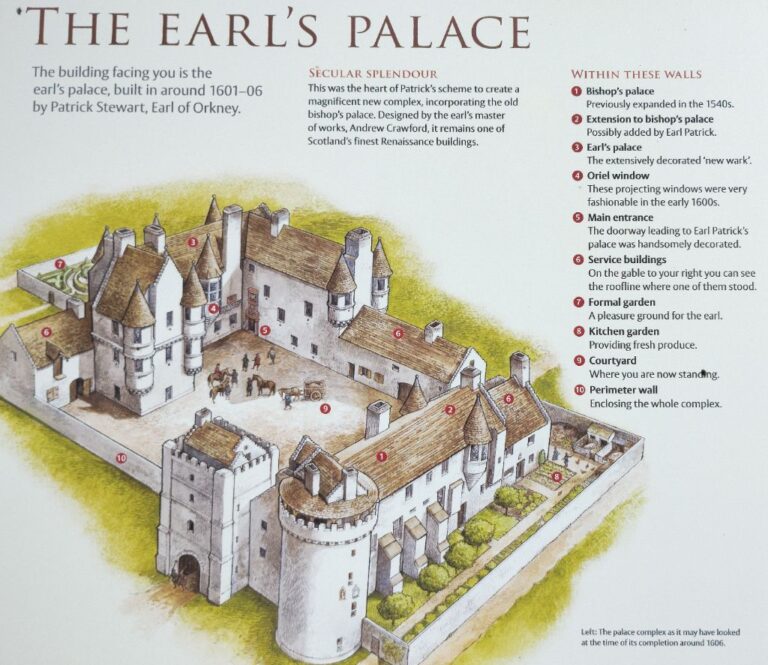

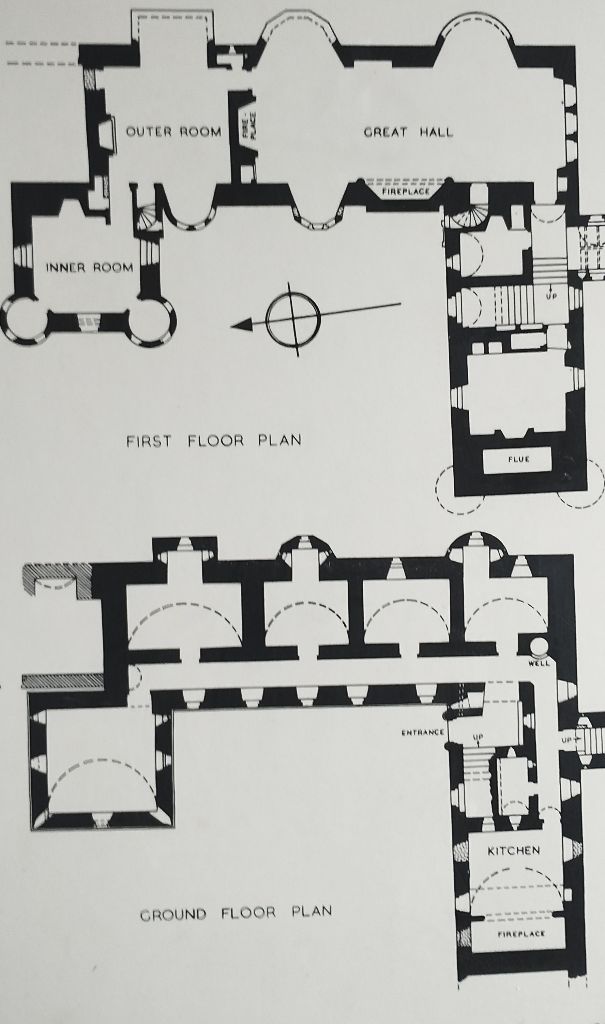

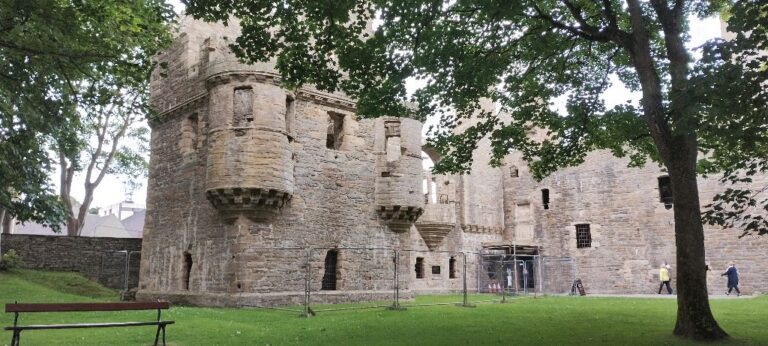

Now we get to the Earl’s Palace. Earl Patrick Stewart (no relationship, that I know of, to the Captain of the Enterprise) was the son of Earl Robert Stewart who was the bastard son of King James V. Earl Patrick had a very grandiose notion of self-worth and the lifestyle he felt was his due.

Earl Patrick is widely acknowledged as one of the most tyrannical nobles in Scottish history.

He wanted to build a more elaborate Palace next to the Bishop’s Palace, but he did not own the land. Not one to be deterred by such a small matter, he fabricated charges of theft against the landowner, then tried and executed him. Impediments no longer in the way, construction of the Earl’s Palace began in 1607.

At one point Earl Patrick attempted to have the Bishops Palace incorporated into his own Palace. This never came to fruition, possibly due to drastically mounting debt he incurred through his lavish lifestyle and financial mismanagement.

Earl Patrick’s brutal treatment of his people and his financial misdeeds eventually led to his imprisonment and subsequent execution.

The last place on our list of things to see in Kirkwall is a strange hobbit-like structure. The “Grain Earth House” is located in the middle of an industrial park. There is no-one on-site and the entry is locked, so one needs to go into Kirkwall and pick up the key before visiting.

Built around 400 BCE, no-one seems to know if the Grain Earth House was used as a storage place, or for some other purposes such as rituals. It could have been used for overnight camping (my guess, as a budding junior archeologist). It seems a bit elaborate, would have required a lot of work to build, and is a bit small to just be a storage locker.

Our Orkney perambulations next take us to the pier at Evie. We had just expected another beach, but found something interesting. Anti-submarine netting, from the Scapa Flow defences installed in WWII, is used to prevent erosion along one part of Evie beach.

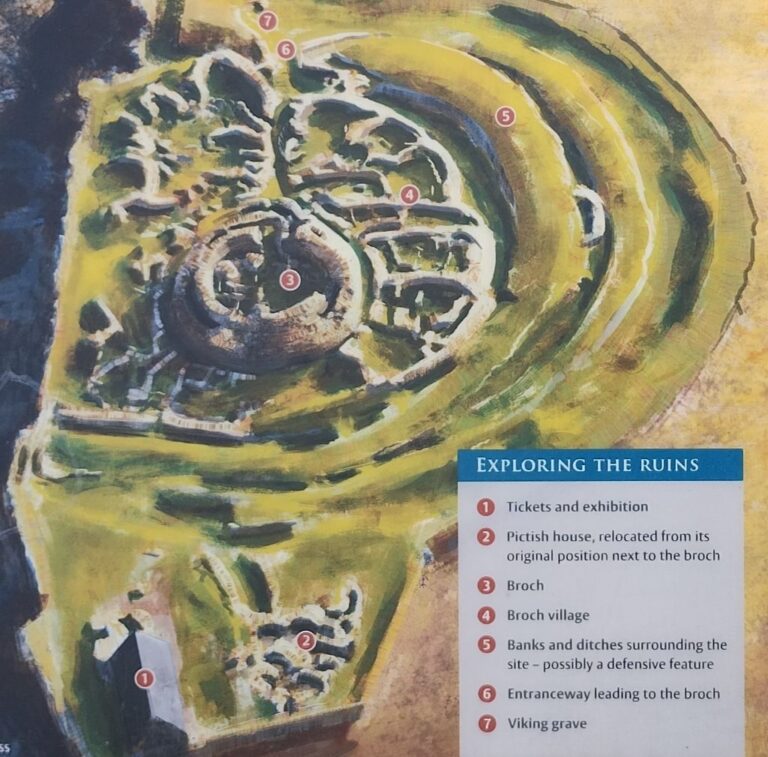

Just along the coast from Evie beach is the Broch of Gurness, the best preserved Iron Age broch village in Scotland.

Brochs are round structures built from stacked drystone (i.e. no mortar). The word broch is derived from Scottish “brough” and means fort. Brochs are unique to Scotland and were built during the Iron Age (about 750 BCE – 43 CE).

Note: I have created a cheat sheet describing the various ages and will post it separately as several previous and upcoming posts will refer to various time periods in Britain and it helps to place certain events into a timeline.

Back to brochs… Some archeologists believe that brochs were also built and used by military groups as they can sometimes be found in strategic defensive locations.

Sometimes brochs are stand-alone structures and sometimes they are located as part of villages (groups of structures).

The Broch of Gurness is an excellent example of a broch located within a village.

Archeologists found a pictish house located on top of a portion of the Iron Age village. Which raises the questions: who were the Picts? When did they live here?

The question of who the Picts were is a bit tricky to answer. The most common theory is that the name “Pict” was given to a group of tribes that lived in northern Scotland during the late Iron Age to Early Middle Ages (see the cheat sheet). There are several theories as to where the name “Pict” came from. My personal favourite is that the word comes from the Latin “picti” which means “painted” (do a Google image search for “picts” and you will get a lot of people with tattoos). Also, the first written use of “Picts” was in a Roman document dated 287 CE.

What happened to the Picts? This quote sums it up for me:

The Picts outlasted the Western Romans by some 500 years until Pictish identity gave way to more contemporary Gaelic Scottish culture. Where did the Picts go? Nowhere. They’re still there in Scotland, cheerfully serving up pints and shearing sheep. [source: Explorersweb.com]

Are the Picts the same as the Celts? Short answer: Yes. Longer answer: the tribes that the Romans labelled as “Picts” are thought to be descended from the “Keltoi” of Central and Western Europe. Ancient Greeks called the barbarians living in Central and Western Europe “Keltoi” [fun note: Greek “Keltoi” also means “the shouty ones”]. The Roman (Latin) word “Celtae” comes from the Greek word “Keltoi”.

If you do a Google search for “pictish art” you will see many images of what we consider to be Celtic artwork. Also, the language spoken by the Picts is a “Brittonic Celtic” language (src: Wikipedia).

We could have skipped all of these questions if those silly Picts has just built their house somewhere else, but nooo, they had to be lazy and decided to steal (sorry: recycle and reuse) some stones that were lying around in nice neat piles (e.g. old walls) .

And now, back to the broch…

The houses of the village around the broch are built tightly together (common walls). Relatively thin vertical stone slabs are used as wall and interior separations. Walking through the buildings is quite incredible, and makes one wonder what this would have been like when in use.

The banks and ditches around the village are thought to have been defensive works. In the above photo of the banks and ditches you can clearly see connecting walls, inside the ditches, that run perpendicular to the outer bank walls. If these are defensive works, why have walls that make crossing the ditches easier? Sometimes archeologists’ theories don’t seem quite right to my layman mind!

Heading west, around the northern tip of Mainland (the name of the island we are currently on in Orkney), is the Brough of Bursay. We are heading there to visit an island that you can walk to at low tide.

The Brough of Bursay is an uninhabited (now) island that is only accessible (without swimming) at low tide. Seeing as how the water is a wee bit chilly we will wait for low tide.

The Brough of Bursay is a popular tourist attraction, and we are at the peak of tourist season, so guess what? It. Is. Busy. The photo of Rosie at night is not a good indicator of how popular this place is. During the day cars are packed-in around us and down the access road. We are parked next to the bus area and buses come and go all day long. Each bus brings dozens of tourists from the cruise ships that dock in Kirkwall. Locals bring their families to play on the sandy beach and explore the tidal pools.

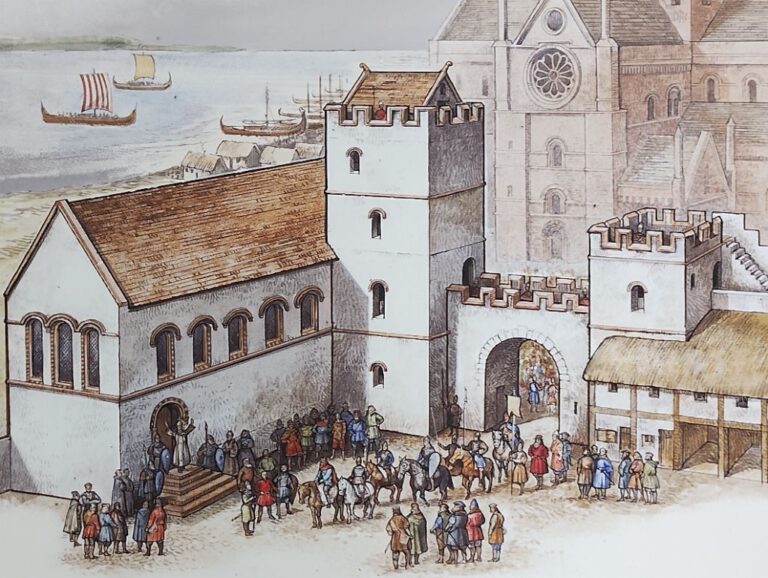

In the previous photo (taken at low tide) the ruins on the left side are of the Norse church circa 1100 CE. The raised grass/stone areas on the right of the photo are the remains of Norse houses dating from 800-900 CE.

The ruins on the island are from three different eras and cultures. The earliest evidence indicates a 6th century Christian habitation, followed by a Pictish fort in the 7th and 8th centuries, and finally Norse houses and a Norse church.

The church ruins have strange pieces protruding from the exterior walls. We have seen quite a few ruins, but have never encountered anything like this before. They make good seats though.

The village of Birsay is a ten minute walk from the Brough of Birsay parking lot. Village may be a bit of a stretch, but there is a small cafe and the ruins of a palace.

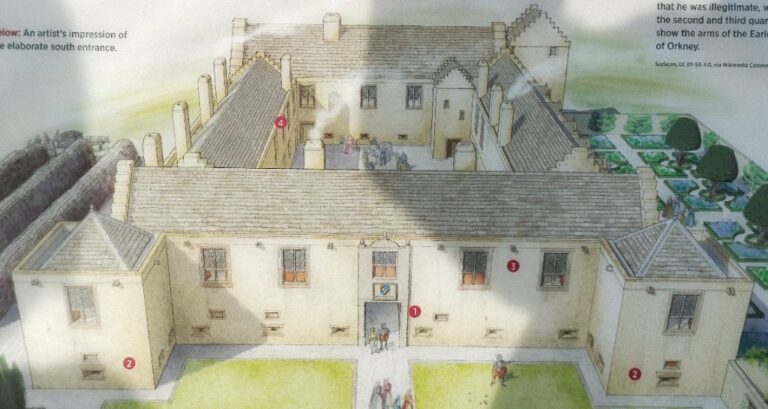

The Earl’s Palace of Birsay was built by Robert Stewart 1st Earl of Orkney in the late 16th century. Robert Stewart was the bastard son of James V, King of Scotland. In 1575 Robert obtained a letter from the King of Denmark-Norway stating that Robert was the King of Orkney. The King of Scotland at the time, James VI, was a bit perturbed by this (Kings tend to be protective of their territory) and imprisoned Robert in Linlithgow Palace.

Another big travel day today, all of 8 miles to our next stop. We don’t seem to have to go far in Orkney to see something different!

Skaill Beach is our next stop, just south along the coast from the Brough of Bursay.

https://room2roam.world/a-cheat-sheet-for-britains-ages/In addition to giving the dogs a beach day, we are stopping at Skaill Beach because it is within walking distance of the Skara Brae prehistoric village.

Note: the “prehistory” period in Britain is considered to be the time when people first came to the island until the time Romans conquered Britain, so from about 900,000 BCE to 43 CE (see cheat sheet).

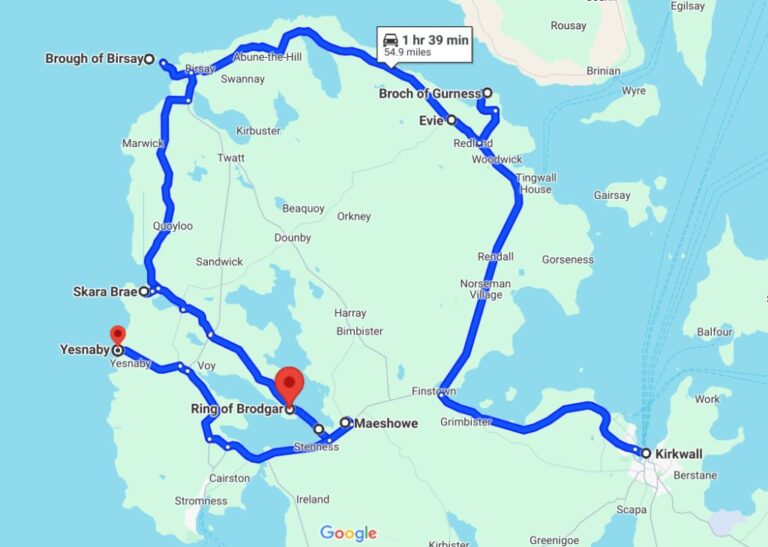

Skara Brae is part of the “Heart of Neolithic Orkney” World Heritage Site. The Heart of Neolithic Orkney also includes the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness and Maes Howe. We visited all of these sites and the Ness of Brodgar, which is not included as part of the World Heritage Site, but is an important archeological dig site located in-between the Ring of Brodgar and the Standing Stones of Stenness.

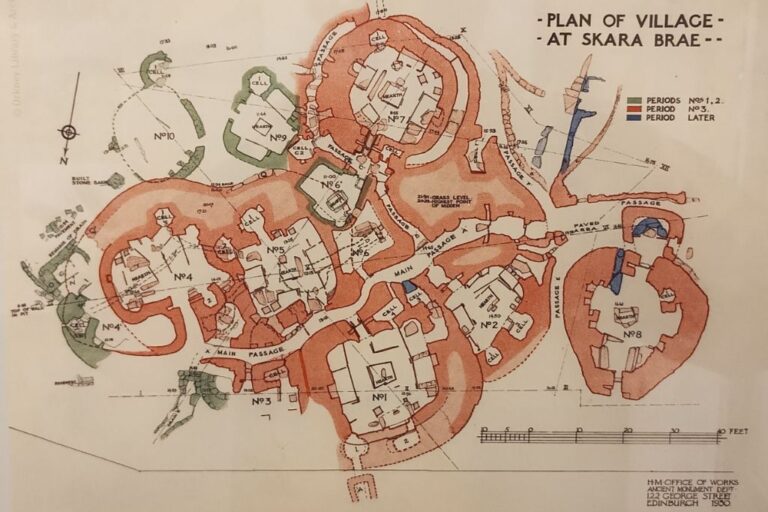

In 1850 a severe storm hit Scotland and uncovered the outline of a stone village. The site wasn’t examined in detail until an archeological excavation was undertaken in 1927 and Skara Brae was discovered.

Skara Brae was a neolithic era (see cheat sheet) village that was built around 3100 BCE and occupied until about 2500 BCE.

In the photo showing “the dresser” there a stone can be seen on the ground just to the right side of the dresser. This stone is called a “quern” which is a hand mill used for grinding grain. The circular depression in the quern is filled with grain and another rounded stone is used to grind the grain in the quern (like a large scale mortar and pestle).

After the execution of Patrick Stewart (2nd Earl of Orkney, son of Robert Stewart; same father and son as described above in this post, a right nasty couple of Scottish nobles) the lands in this area of Scotland were given to the Bishop of Orkney. In 1620 the Bishop of Orkney built a small manor house, in the Bay of Skaill, which is now known as Skaill House. The Bishop’s son became the laird of the manor and property and was subsequently passed down to succeeding lairds.

Skara Brae is located in the backyard of Skaill House.

Our next stop, about 6 miles away, is the Ring of Brodgar. I am really liking these short driving days!

Believed to have been erected around 2500-2000 BCE this is a late Neolithic, early Bronze Age (see cheat sheet) henge and stone circle. “Henge” means a flat area, usually circular, surrounded by a ditch.

The Ring of Brodgar originally was made up of 60 standing stones in a circle, but only 27 remain. The photo at the top of this post shows the Ring of Brodgar at sunset.

The purpose of the Ring of Brodgar is unknown, but theories abound! Ceremonial location. Religious place of worship. Used for astronomical observations. Meeting place. Make your own guess!

One-half mile down the road is the Ness of Brodgar, an archeological dig site that has been under active investigation since 2004. This year (2024) will be the last year of on-site digging at the Ness of Brodgar as they are filling the dig site back in to protect the unearthed structures from weather damage.

The site was discovered when a farmer’s plow pulled up a price of a stone cist (box) in 2002. Since excavation started in 2004 eight major structures have been found on the site. The current understanding is that these structures served as a communal meeting place and that people travelled to come to here, but no one actually lived here. Additional finds include: over 850 decorated stones, over 1000 tools, over 5000 pieces of worked flint/stone, over 90,000 pieces of pottery, and over 100,000 bones (mostly animal). The official excavation web site (www.nessofbrodgar.co.uk) contains an incredible amount of information about the Ness of Brodgar.

Moving down the road another mile brings us to the Standing Stones of Stenness.

Excavation has shown that the Standing Stones of Stenness are a henge monument and possibly the oldest in the British Isles, built about 3100 BCE. There is at least one hearth in the monument an excavated pottery and animal bones show that Neolithic visitors cooked and ate here. Again, like the nearby Ring of Brodgar, the exact purpose of the Standing Stones of Stennes is not known.

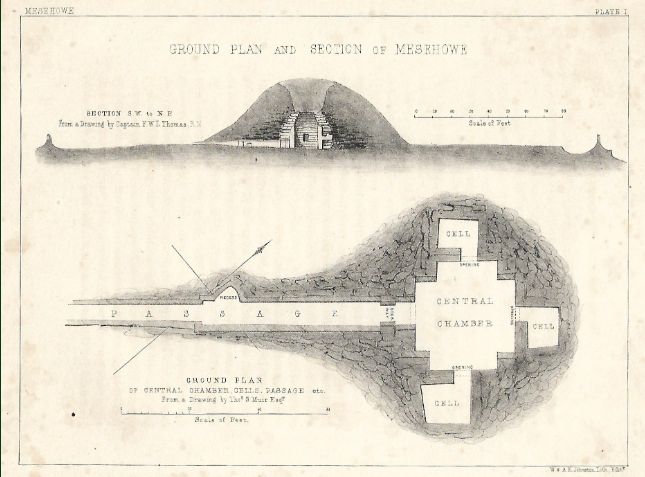

About a mile away from the Standing Stones of Stennes is Maes Howe, a Neolithic Chambered Cairn built around 2800 BCE.

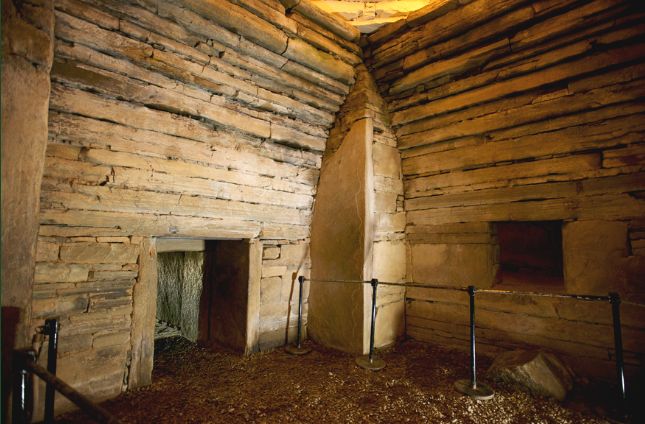

No photography is allowed inside Maes Howe.

A 36 foot long passageway (about 3′ in height) leads to the interior. The roof of the passageway is a single slab of stone. Quite impressive to see (no photos, so you’ll just have to imagine a single solid piece of stone over your head as you crab-walk along a narrow passageway in the dark).

Once inside, the roof opens up into a high 15′ stone-roof central chamber about 15′ on each side, with three small openings leading to small side chambers. A Neolithic hotel? “You can check in any time you want, but you can never leave…” (Eagles reference for you philistines).

The long entrance is aligned with a standing stone (the Barnhouse Stone) to the southwest. Only on one day of the year, the Winter Solstice (shortest day of the year), does the Sun align with the Barnhouse Stone and project light through the entrance passageway and light up the interior of Maes Howe (those Neolithic types were pretty smart, and observant).

Time for some newer (and more alive) than Neolithic ruins. It’s time for the Dounby Agricultural Show!

There are 5 regional agricultural shows leading up to the final big show in Kirkwall. We won’t be on the island for the final show, but the Dounby regional show is being held on the day we leave. Our ferry doesn’t leave until the evening so we can stop by for a few hours to see what all the fuss is about (locals keep telling us that an agricultural show is a must-see event).

The fun starts before we even get to the show as we don’t think we can park Rosie anywhere near the show, so we decide to take the shuttle bus from downtown Kirkwall. The fun part is getting the dogs on the bus. The bus is packed. Apparently there is a lot of interest in the Dounby show, so the dogs have to find a spot on the crowded bus. Lump is a little unsure, but eventually settles on the floor. SweetPea has no problem at all, and immediately cozies up to some stranger and demands some attention… which is quickly forthcoming!

We didn’t enter Lump and SweetPea into the Dog competition as it would have been unfair to the locals if “dogs from away” would have won all the prizes, totally objective dog parents here 😉

Besides, our dogs were much too distracted by eating all the chips (french fries) that were being dropped on the ground all around them by people moving while eating and watching the events!

Our time on Orkney is done (we have also spent some time in Shetland, but that is the subject of another post), so one last visit to the coast before we get on a ferry to take us back to the Scottish mainland. On final stop in Orkney is Yesnaby, located on the west coast of Orkney Mainland.