We heard that a town called Findhorn had one of the best beaches in the UK, so it is worth a visit.

We are staying at the inelegantly named TFVCC Motorhome Stopover which is located in the dunes next to the beach, which is just past the town. The last kilometer or so of the drive is through the town of Findhorn and not only are the streets narrow, but there are cars parked all down one side. We proceed down the street at about 2 mph, trying not to knock off the mirrors of the parked cars. We get past a long row of parked cars and then have to make a tight right turn around a building (the building is built right on the corner). One more turn (left this time, no building trying to leap out in front of us) and we are out of the town and can see the parking area in the dunes. Phew!

We later discovered, during a conversation with a local, that the local buses and lorries drive on the sidewalk (or “pavement” as they call it here in the UK). This would have made our drive through town a wee bit easier. Oh well, we made it and didn’t kill any mirrors in the process.

The photo at the top of this post was taken from Findhorn beach on a cloudy evening.

Findhorn beach is a 7 km long stretch of sand. There is a trail, suitable for walking or biking, that runs in the dunes and trees above the beach.

We took our fat tyre e-bikes and headed out through the dunes. The trail meandered through a lot of grassy land and then we started seeing gorse bushes along the trail. One stretch of the trail had solid gorse bush on both sides, so falling over would be a bad idea.

We left the grassy/gorsy area and entered a nice flat sandy area under a small forest of pine trees whereupon I immediately got a flat tyre. First flat on the new e-bikes. Good thing we had a patch kit and pump! A few minutes later and we were back on the trail. Our fat tyre e-bikes work great in the sand, even the soft sand is traversible (more power Scotty!).

We emerge from the tree-lined trail into a holiday home park. We think that we must have missed a cross-trail somewhere. A quick check back down the trail reveals… nothing. So back to the holiday home park where we follow the asphalt lane until we exit the park and find we are in the town of Burghead, which is the other end of the beach from Findhorn.

We see a ramp down to the beach and think that we might be able to bike along the beach all the way to Findhorn. That could be fun!

The beach is mostly deserted, with only a couple of places where car parking areas enable people to access the beach. Most of the 7 km of beach is all ours! E-bikes make riding in the sand easy, and is great. The trail through the dunes and trees was nice, but cycling on the beach is at a whole other level of fun!

After a couple of beach days it is time to move on. We leave the parking area reasonably early in the morning and there aren’t many cars parked on the road through town, so there were very few car mirrors to dodge.

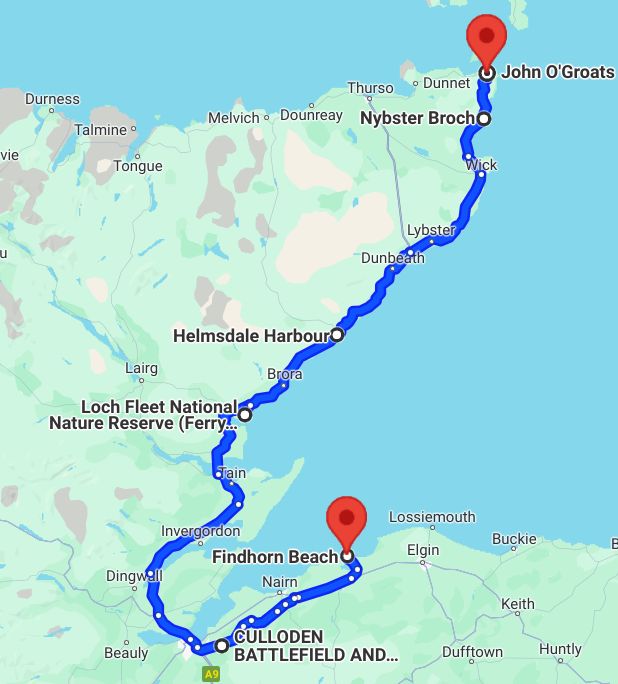

We are heading to the Culloden Battlefield, located just east of Inverness. The 1745 Battle of Culloden ended the final Jacobite hopes of a Scottish King on the throne of Scotland or Great Britain. There is a visitor centre on the grounds of the battlefield that houses a museum that provides a good account of the events leading up to the battle and the battle itself.

Jacobitism got its name from “Jacobus” which is Latin for “James”. In 1688 James VII (from the House of Stuart) was deposed as the King of England, Ireland and Scotland (note: just to further confuse things, James VII was known as King James II in Scotland). His supporters became known as Jacobites, and Jacobitism was the political movement whose goal was the restoration of the House of Stuart to the throne of Scotland.

The first Jacobite rebellion took place from 1689-1692 and was largely confined to the Scottish Highlands. After the 1707 Treaty of Union, which joined the Kingdoms of England and Scotland to become Great Britain, Jacobites expanded their goal and sought the throne of Great Britain for the House of Stuart.

The second Jacobite rebellion took place in 1719 and was supported by Spain, who was currently at war with England and believed that a Jocobite rebellion would distract English forces. It didn’t end well for the Jacobites, and the Spanish invasion of England was called off because the Spanish fleet was badly damaged by a storm.

The final Jacobite rising, or rebellion didn’t go as planned from the beginning.

In 1743 the French and Spanish agreed to help the Jacobites. France and Spain were again at war with England, and supporting a Jacobite rebellion was thought to be a cost effective means of displacing English forces. In 1744 transports holding 12,000 troops left France. A storm sank several ships and damaged others. No troops made it to Scotland.

France would not commit any more troops to the Jacobite cause, but allowed 100 volunteers and a supply of weapons to be loaded onto two ships. Charles Edward Stuart (aka Bonnie Prince Charlie) joined the ships in France and they headed to the Outer Hebrides (western Scottish Islands). These ships were intercepted by the British navy. The ship carrying the 100 volunteers and armaments was forced to return to France. The ship carrying Charles Stuart made it to Scotland.

Despite the loss of men and arms, Bonnie Prince Charlie decided to proceed with the rebellion.

Gathering supporters as they moved through Scotland the Jacobites eventually entered Edinburg unopposed. Edinburg Castle was still held by the British, but the Scots proclaimed James II as the new King of Scotland (note: James II was on vacation in Rome at the time and Prince Charles was doing all the heavy lifting for him).

The Jacobites decided to invade England to ensure ongoing support from France and to remove the current King from the throne of Great Britain. Bouyed by a series of successful battles and growing with the influx of supporters, the Jacobite army quickly moved south.

They made it as far as Derby (about 120 miles north of London) when they decided to turn around. Prince Charles wanted to press on to London, but the rumoured threat of a British army heading to Scotland (which the Jacobites had left undefended) and the lack of supplies and money led the Jacobite war council to overwhelmingly vote to return to Scotland.

The Jacobite army that returned to Scotland and its forces were split up to put down an insurgency in the Highlands (led by Scottish clans loyal to the British throne) and others were sent to besiege Stirling Castle. At this time a well supplied British army had made its way past Aberdeen and was closing in on the remaining Jacobite forces.

The Jacobite army had no heavy artillery and was very low on supplies. In a desperate move, Prince Charlie led a smaller group in a night attack on the British army camp, but the attack never happened. The attacking Jacobites became strung out during the night run to the British army and were unable to meet up to coordinate the attack.

The Jacobites, tired from the lack of food and from the previous night’s exertions were in poor shape when the British army appeared the next day. The Jacobite war council decided to make a stand instead of losing by attrition to the better supplied British army.

Less than 5,000 tired and hungry Jacobites met a well fed, rested and supplied army of 7000-9000 British troops.

The two opposing forces met at Culloden (pronounced “cull ODD en – emphasis on ODD). As per usual at the time, the two forces lined up across from each other. However, the British army did not move to attack. Instead they remained in position and used artillery to pound the Jacobite lines. The Jacobites, not having any artillery, were unable to respond in kind. If they stood in position they would eventually all be killed, so the command was given to charge the British lines. The ground between the two forces was extremely boggy and the Jacobites were very slow in crossing, giving the British artillery a lot of time to reduce the oncoming attackers.

The battle lasted less than one hour with a decisive win for the British. An estimated 1200-1500 Jacobites were killed in less than one hour with the British losses of only 50.

The British took 500 prisoners with the remaining Jacobites, including Prince Charles, evading capture and dispersing.

Thus endith the Jacobite movement in Scotland, and Bonnie Prince Charlie escaped to Italy where he died an alcoholic.

The actual ground where the battle took place just looks like a field now. Flags have been placed in the field to mark the starting location of the Jacobite and British lines.

One last note on the House of Stuart. The original name was the House of Stewart. Mary Stuart (aka Mary I of Scotland; aka Mary, Queen of Scots), of the House of Stewart, was brought up in France and changed the name to the french spelling “Stuart”.

History lesson is now over (I promise), although it is incredible how much history there is here. Thousands of years, and a lot of it accessible for those who are interested.

We are now heading north along the east coast of Scotland and it is time to see some wildlife, or at least what passes for wildlife in a country whose largest predator weighs in at a whopping 10 kg. Although, if the bunnies in the UK ever got organized they could probably take over a huge chunk of the country because there about 38 million of them (I kid you not, stats from the UK Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust). And you really need to watch out for the ones with fangs!

The Loch Fleet National Nature Reserve is a tidal basin fringed by sand dunes and a Scots pine (of course, what other kind of pine would it be here in Scotland) forest. No Jabberwocks or Bandersnatches here, but there are lots of birds (which SweetPea loves to chase down the beach).

We met some locals in the parking lot and one was from a small coastal town not too far north of us. Helmsdale we are assured is well worth a vist. So guess where we are headed to next?

Along the way is a broch called Carn Liath. It’s right along the highway, so easy to stop in for a quick visit.

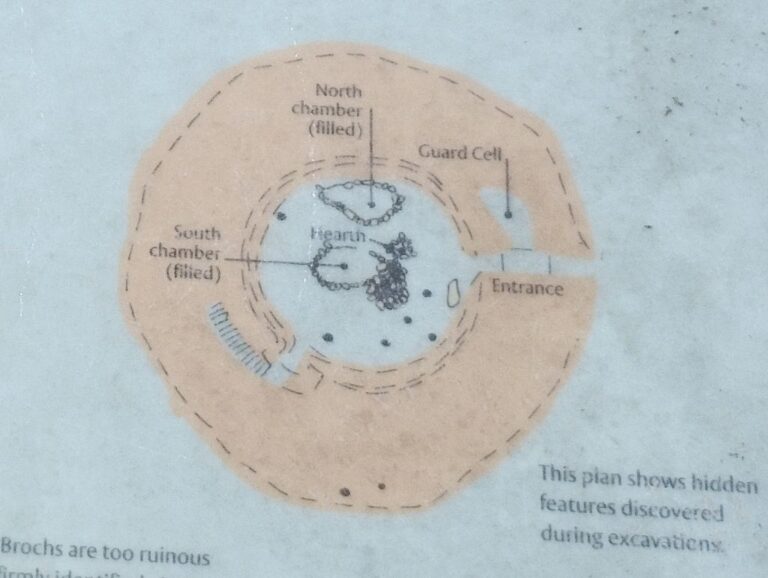

Built on a bronze age site, Carn Liath is an Iron Age broch. Brochs are unique to Scotland. These round structures, built from stone are believed to have been used as domestic residences and storehouses. Other archeologists believe that brochs served military purposes. No one knows for sure, so pick your favourite theory, or make one up yourself. We have discovered that archeology is an inextact science and one theory is just as valid as another!

Brochs range from 10 m to 20 m in diameter and have walls up to 3 m thick. Walls can contain rooms and stairways (perhaps this is where the idea for building stairways inside castle walls came from).

Brochs had internal structures made of wood which provided additional living and storage space. Broch roofs are thought to have been made of wood and covered with thatch or turf, but the idea of whether brochs had roofs or not is still under discussion. I think they had roofs, as who would build a house without one?

Based on a local’s recommendation Helmsdale is our next stop.

Helmsdale was planned and developed starting in 1814. It was intended to house some of the tenants that were evicted during the Highland Clearances (aka Scotland Clearances) .

The Clearances that took place during the 1750-1860 time period and involved the eviction of tenant farmers (crofters) who paid rent to the local land owner (lord, earl, duchess, etc). After the farming tenants had been removed the land was used for raising sheep which generated much higher revenues for the land owner.

A Canadian connection: some tenants evicted during the Clearances ended up in the Red River Settlement in Winnipeg, Manitoba courtesy of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Elizabeth, Duchess of Sutherland, created the town of Helmsdale with the intent of starting a fishing village that would provide additional revenues, using the displaced farmers as labour for the fishing industry. Herring was discovered off the coast and Helmsdale became the home port of one of the largest herring fleets in Europe!

There is a small community museum called Timespan, which has an incredible wealth of information regarding the creation of Helmsdale, the evolution of the fishing industry, and a description of a brief local gold rush.

Our next stop as we continue north up the coast is Nybster Broch.

Funny story about Nybster Broch. We couldn’t find the broch! We found a strange monument that looked like it was built in the 19th century, but was adorned with gargoyle statues from a much earlier period (as evidenced by a much greater degree of erosion). In our defence, the grass was about 3′ tall and we couldn’t seeing anything more than a few feet away from the mown path. A few weeks after visiting Nybster we saw a picture of the broch and it was right behind the monument! Can’t believe we couldn’t see it!

There was a small rocky cove nearby and a great walking path along the edge of the cliff wall, so all was not lost.

Next up is our last stop in mainland Scotland, John O’Groats (JOG). JOG is a tourist town. If not for the tourists there would be no town. Nothing here to see… except the views. To the east, sea and more sea. To the north, some sea, but more importantly, islands. Orkney Islands to be precise and our next destination!